An altared state

Last Words project offers chance for final farewells

Death can come after a long illness or completely out of the blue, but for loved ones left behind there is no such thing as perfectly prepared. Death doula, grief counselor and art therapist Crystal Akins, founder and executive director of Activate Arts, has made it part of her life’s work to help people meet the challenge of moving on with grace.

“Some people never got to say goodbye, or regret not saying something while they still had the chance,” she said. “Writing a letter to that person is a surprisingly effective way to get some peace.”

To facilitate this healing tool, Akins has spearheaded an art project that has an ultimate goal of raising money to help people that may otherwise die completely alone.

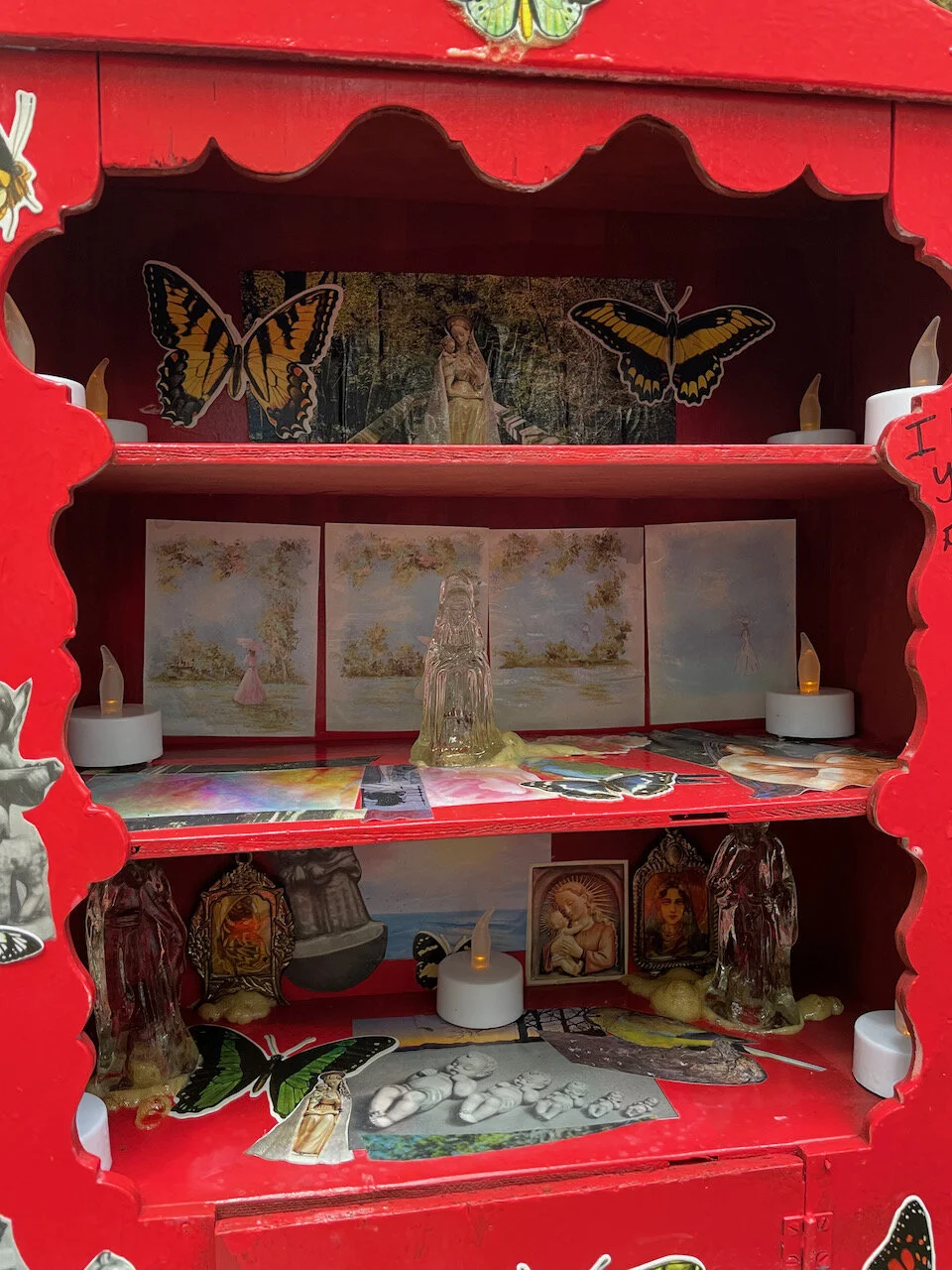

Three visually arresting Last Words Mailbox Altars were recently installed in Lincoln City: at Josephine Young Memorial Park, Siletz Bay Park and Nesika Park.

The brightly colored altars that will remain in place through the end of June, include supplies for letter writing and a locked box to deposit them in — and are also open for artistic contribution.

“We have little cubby holes where people can leave rocks, sticks, flowers; anything that feels symbolic or has some meaning to them,” Akins said. “But mostly it’s about the letters; something you can do with no fear of judgement.”

This first round of the project will end in the fall with the Last Words Cemetery Concert Series in Portland, featuring songs inspired by the letters and other experiences Akins has had in her death work. Proceeds from the concert and CD sales will go toward Oregon’s first death with dignity care space for unhoused, terminally ill veterans in Multnomah County.

“I’ve been asked why we are starting the project in Lincoln City, but where do people go for peace?” Akins said. “So often they come here, to the beach, so I think it’s the perfect choice.”

Akins has been dreaming of getting this project off the ground for a while now.

“Having the altars up and reading the letters makes it real,” she said.

As Akins reads the letters she has noticed few sentiments that come up again and again.

“Almost all of the letters say two things: ‘I love you,’ and ‘I’m okay,’” she said. “It just really shows you that we’re almost all going through the same thing when we have a significant loss.”

The loved one doesn’t have to share your species, though.

“I’ve been asked if it’s okay for people to write a letter to a pet,” Akins said. “Of course it is; your loved one is your loved one.”

The project has come partially from Akins’ work with children and using imagination to process a trauma.

“I’ll ask kiddos to make up a positive scenario and then really try to picture it happening,” she said. “Using the imagination in this way can help to create new pathways in the brain. Writing letters is a similar exercise.”

Her responses from the community have been mixed, but she clings to the overwhelmingly positive ones.

“So many folks are responding with gratitude,” she said. “Some are still afraid to have a conversation about death so they push back in different ways, but that’s okay too. I’m here when they are ready.”

The signs on the altars that instruct people how to participate make it clear that the letters will be read, and possibly used in a song.

“It’s such an honor to read the stories,” she said. “I love being able to invite people to work with their grief, and we are very clear that we don’t want people to put any personal information that could identify them or the person, or pet, they are writing to unless they really want to.”

Akins says this project is a small way to help people who might need but are not ready for grief counseling.

“Grief doesn’t go away, it just changes,” she said. “If you don’t talk about it there’s always going to be this part of you that can’t quite move on. Writing a letter is a great first step.”

For more information, go to the Last Words Project page on Facebook.